Down the Kasai River

Down the Kasai RiverI had a train reservation north from Luluabourg with it horrifying cannibal war to the end of the line at Port Francqui. There I would take the riverboat down the Kasai River to the Congo River.

The Belgian Government back in Brussels had stopped all money from going in and out of the Congo so that those whose savings were in Congolese francs would have worthless paper after Independence rather than Belgian francs.

Because of the embargo on all money transfers, I had only $36 in travelers’ checks above the cost of my boat fare.

The train from the south was a day and a half late, but it did get through, which surprised the station master.

The train was again old Wagons Lits cars, which were not too clean but comfortable, and elegant with plush, brass, crystal and inlaid wood.

That night the train to Port Francqui just crawled along. At one stop a band of hungry Baluba tried to steal the dining car.

The next day, the train never proceeded at more than 20 mph, and at every cluster of African huts along the track people piled on and off from the African cars which were in front of the engine.

There was no longer much food for sale by the trackside and I was hungry, having eaten my provisions for the journey while waiting in the Luluabourg station for the train to arrive.

All through the long, hot day, the old wood-burning engine wheezed slowly across the grassy savanna, and dipped down into steamy jungle valleys, where streams wandered for miles without the light of the sun striking their waters.

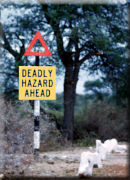

At one point, on the side of a slope, our train had to stop for repairs which took three hours. The Europeans got their weapons out of their luggage and loaded them, but the train was not attacked.

The conductor came into the dining car where everyone had gathered, to announce that dinner would be served in half an hour.

“Who are we having?” asked a gray-bearded White Father, with the brittle humor of war.

Those of us who were sober laughed in a release of tension. Others in the dining car had drunk themselves into merciful oblivion.

We arrived in Port Francqui late in the afternoon and I was informed by the OTRACO riverboat people that besides the ticket, passengers must pay in advance for three meals a day. The fee for meals was $12.80 per day and I had only $36 beyond my boat fare me and no way of getting money sent to Port Francqui. Then I found out OTRACO wouldn’t accept the travelers’ checks that I had for my passage on the boat!

I went up to the town to cash the travelers’ checks, but the bank had packed up and left two days before.

When I inquired about the Post and Telegraph office to wire the American Express representative in Leopoldville, I was informed I’d missed the post office by only a day

The OTRACO people just shrugged and told me it was my problem.

I envisioned myself stuck there while the town disappeared around me.

Finally the OTRACO manager agreed to radio Leopoldville to see if something could be arranged. I went back up the hill to wait in the hotel lobby with the other passengers.

The town was small and unprosperous looking, and now it was half deserted as well.

The old hotel was built and run by the Wagons-Lits Company. It was large and rather splendid in a Victorian colonial way, but now it was as desolate as the rest of Port Francqui.

The hotel lobby looked like a corner of some prop room. It was piled with an incredible assortment of things- round-topped, brass bound trunks that were green with mildew, Edwardian clocks and figurines, fishing rods and guns, mothy trophy heads with missing glass eyes and straw leaking out the cracked noses, and pathetically, old baby buggies.

The settlers who had come down from Belgium two generations earlier, could never have envisioned a return under such circumstances to the Europe they had left behind. Now their descendants sat dazed, amid the pitiful salvage of their lives, facing an unknown future.

Out on the verandah a small group of white Congolese sat drinking beer and ignoring their shrieking, running, wailing children, who upset chairs and pummeled each other.

One of the other passengers from the train came over to me and urged me to come along with him as they had made a great find.

The find, a few blocks away in the town. It was a small but modern supermarket, complete with carts, that had a big sign in the window that said in French - “Wall to Wall Clearance Sale.”

We went in and found the other train passengers buying large bags of the greatest bargains I’d ever seen. Caviar from Russia at 20¢ an ounce and the frozen foods were being sold for practically nothing.

When the passengers had bought all they were going to buy and started to leave, the owner’s wife, who was sitting behind the cash register wearing a flowered hat, emptied all the money from the drawer into a shopping bag and walked out behind us tossing the keys to the head African clerk.

The owners were Portuguese. They came to profit and over the years they had. This was a setback, but they could toss over the keys and walk away.

But I still had my problem. How to get out of the Kasai?

Except in the center of the main towns, the roads in the Congo were just dirt tracks, many with grass strips between the tire ruts and impassable in the rainy season.

The Belgians had been fortunate to find in the Congo an excellent, natural trans portation system of waterways.

The major rivers, the Congo, Lualaba, Kasai and Ubangi, and their tributaries, totaled more than 8,000 navigable miles, and the eastern border was lined with a chain of great lakes.

Most of the river boats were tiny Victorian relics, half rusted away and painted the color of rust so it wouldn’t show. Many of the larger riverboats had been towed across the Atlantic after outliving their usefulness on the Mississippi. These were big, old-fashioned, flat-bottomed, stern wheelers that drew only a few feet of water.

The Belgians had constructed railway links between the water systems.

The major towns were served by Belgium’s national air line, SABENA, which had a monopoly in the Congo. SABENA would greedily guard that monopoly through June 30th, even though SABENA did not have enough planes to transport all the Europeans who wanted to escape the interior.

Other forms of communication were as inadequate as the roads. There were only 13,000 telephones in the whole of the Congo and Ruanda-Urundi, and no phone service at all between most cities.

The riverboat was my only way out of the Kasai.

The sun was a vast scoop of tangerine sherbet sliding towards the horizon, when the OTRACO manager came up to announce it was embarkation time.

He told me that American Express Company’s representative in Leopoldville would guarantee the price of my ticket against the our family credit card.

When we arrived at the river front, Congolese were piling wood into the open engine deck of the side-wheeler, and some other Africans were manhandling the supermarket owners’ Volkswagen up a couple of wooden planks onto the top of the long, low, barge which was in front of the riverboat.

Lashed to the far side of the barge was a small, old, brown riverboat, which no longer traveled under its own power, but served as second and third class accommodations for the numerous African passengers.

Many of the Africans had brought four-legged passengers. Several goats bucked and bleated as they were dragged up the gang-plank, and one African had a three foot long crocodile in a reed sling, its snout tied shut.

The top of the barge was about four feet above the waterline, and the river ran coolly by and most of the Africans preferred the barge top to their river boat.

A missionary’s car was put aboard next, and he stood in the panoramic window of our dining room, which was even with the prow of the boat, taking movie film of the process to show the mission board.

I put my things in my cabin. It was small and spartan and entirely white.

I went back out onto the deck.

This was a rather small river boat and there was only one passenger deck. In the front was a dining room and bar, that also served as a lounge. The tables were arranged around the panoramic window and overlooked the barges and African boats, the river and the jungle.

I went off by myself, back to the stern, and watched the sun drop behind the towering jungle. This was what I had imagined most of Africa would be like, but it was the first expanse of jungle I had seen.

These mighty African rivers flow across the high central plateau of the continent, then plunge down to the coastal lowlands.

Africa is not spectacular for the height of its landforms, but for the vast distances they extend. In Africa, as on the great deserts, one is awed by space — the plains that spread from sunrise to sunset, the rolling hills that seem to follow one another into infinity.

At 10:30, I was alone in the lounge reading a tattered paperback of ‘The Brothers Karamazov’. After a few games of backgammon, the Belgians had retired for the night. If they had been British the singing and yarning would have gone on until long after midnight.

Suddenly the hot, humid air became charged with electricity. I went out on the deck and watched the sky blacken with storm clouds. A violent wind came up that whipped the leaves of the dense jungle foliage along the bank. Then I heard a sound like a fire hose on a tin roof as a line squall moved up the barges towards us. I ran out on the deck to greet the storm.

The huge, driving drops of rain came down in solid sheets and the air in the squall was 200 cooler. I stood there with the rain running through my hair and soaking my clothes. I turned my face up and let the sweet water pour into my mouth and If the deck hadn’t been so slippery, I would have danced in the rain like the children did that day in Saigon, when it rained out of season.

I climbed the steps to the top deck where the bridge was and the European officers lived and where the Captain’s wife had a little cabin like a cottage, with flowers and all.

I poked my head through the open door to the bridge. “Sight seers allowed?”, I asked.

“Sure. Why don’t you work that hand spot for us?”

The powerful spotlight struck the sheets of rain and glared back into my eyes. Then I saw the bank; vines and great shiny leaves overhanging a steep muddy slope that was bleeding red, laderite soil into the river.

All I could see in the wheelhouse was the orange tip of the captain’s cigarette which glared yellow when he drew on it, and the pilot’s disembodied face floating eerily green in the glow from the binnacle—like radar scope.

“Cinq metres!” I shouted over the din of the torrential rain on the roof.

The captain was at the wheel and swung the riverboat away from the bank until once again all I could see was the rain. Back behind us, the navigator called out his calculations from the dimly lit chart room.

I searched through the beaded curtains of rain for the next hour, calling out whenever I saw the bank.

Of course it was insanity to be navigating at night in such a storm but it was even less safe to tie up.

That hour in the wheelhouse, in the tropical rainstorm that drowned out all other sound and washed the air clean was one of the most marvelous I have known.

I have always liked storms, the wilder the better. As a child I liked to go up into the mountains when the wild summer storms came, and stand in the wind and the driving rain with the lightning playing about me. It was dangerous, but being part of the pure, wild power of the elements gave me a sense of exhilaration like no other.

By midnight, the rain stopped and the spotlight could be fixed to shine on the bank a hundred yards down stream as our riverboat and the dark, oily smooth river continued on our mutual journey to meet the mighty Congo.

The next day, we were lined up along the rail watching Africans carrying wood aboard at a fueling station, when one of the missionaries suddenly turned to us.

“It’s not a failure of the Christian principals we’ve instilled, it’s a matter of protein need. They are fighting a war, so they must have protein. The bodies of their enemies are the only source of protein available.”

But, as I had seen, the cannibalism in the Congo was also used as a form of terrorism. Very soon there were so many bodies that only the rump roasts were removed and the rest left to rot. Entrepreneurs saw the commercial value of what the warriors left behind, and the government had to pass a law that no meat could be sold without some of the hide attached.

After a hasty refueling, the riverboat pulled away from the bank where it was so vulnerable.

The Kasai River was quite wide but the navigation channel was near the shoreline, and so we had an excellent view of the jungle and the villages as the boat moved along. In some sections, the river split into many smaller streams through marshy flats, where we could see for miles. Then it came together again between steep jungle banks with gashes cut by the rain where the red earth ran down into the river.

About every half hour we passed a village set in a clearing. Some villages had nets hung out to dry and dugout canoes, because they were fisher people. Others had great piles of wood in front of them because they made their livelihood selling fuel to the riverboats.

At noon, I went over to the African boat, looked around, and to see what it was like, bought a meal from their kitchen, to the horror of the First Class purser. It was bland corn meal mush and some boiled fish.

We arrived at Banningville the next afternoon.

Banningville was an important communications center where the tributary Kasai joined the mighty Congo River.

The land was hot and flat, with dense jungles.

It surprised me to see the local women carrying their burdens in a basket on their back supported by a strap across the forehead, which was in the manner of mountain people.

Women in flat country else where in the Congo balanced burdens on their heads, usually in a white enamel basin with a kerchief securing it’s contents. It always astounded me to see women walking with empty 20-gallon oil drums balanced on their heads, but then, how else could one person carry a 20-gallon oil drum?

Because of their method of carrying, the women of Banningville were bent and graceless, in distinct contrast to the stately women with beautiful posture in other parts of the Congo.

While I ate supper, I watched the crew attach still another Third Class boat to our side and put even more barges out front. By the time we sailed at midnight we were a flotilla.

The next day, the open decks of the Third Class boats were spread with drying fish and the stench was so awful that the Europeans spent a great deal of time one the prow of the first barge, upwind of the fish, instead of lounging besides their cars. But most of the sunlit hours were too hot to go out by the cars, so the stink had to be endured.

The barge tops out front of the riverboat were classless territory, shared by the Africans and the Europeans, and both groups amused themselves by noting the peculiarities of the other as we sailed through vast stretches of swamp, broad miles of flat, barren land, and finally hills that looked rather like Wales, on our way down downstream to the great Congo River.

There was a lot of mail waiting for me in Leopoldville, including clippings from the American papers where my stories on Luluabourg had run on the front pages above the masthead. There was also a cable from the publisher, “Send more about cannibals” it said. But when I read the stories in the papers, I was furious- the ‘cannibals’ were all they had used, cutting out the political and economic material entirely.

I composed a cable on just the political situation and took it across the Congo River’s Stanley Pool to French Equatorial Africa, where the French were happy to transmit the story of the chaos in the colony of their rivals in Africa, the Belgians.

Patrice Lumumba was the arch fiend in the Belgians’ pantheon of black political devils. They said he was a raving madman, and they also said he was diabolically clever, but he was the most important man in the Congo, so I would have to go far up the Congo River, deep into Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, to seek the truth about this man Lumumba.

I was alone in the lounge reading a beat-up paperback copy of The Brothers Karamazov. It was only 10:30, but after a few games of backgammon, the Belgians had retired for the night. If they’d been British they’d have been yarning, singing, and telling jokes until after midnight.

Suddenly the hot, humid air became charged with electricity. I went out on the deck and watched the moon and stars disappear behind storm clouds. A violent wind came up that whipped the leaves of the dense jungle foliage along the bank. Then I heard a sound like a fire hose on a tin roof as a squall line moved up the barges towards us.

Soon the huge, driving drops of rain were coming down in solid sheets and the air in the squall was much cooler.

I stood there with the rain running through my hair and sticking my clothes to my body which was a treat after the coffee colored river water that came out of our taps and showers, carrying in it the danger of disease.

I climbed the steps to the bridge deck. There on that top deck the European officers lived, and the Captain’s wife had a little cabin like a cottage, with European flowers.

I poked my head through the open door to the bridge. “Sight seers allowed?” I asked.

“Of course. Why don’t you work that hand spot for us?”

All I could see in the wheelhouse was the orange tip of the captain’s cigarette, which flared yellow when he drew on it, and the pilot’s disembodied face floating eerily green in the glow from the binnacle-like radar scope. Behind us from the dimly lit chartroom, the navigator called out his calculations.

As I swung the powerful spotlight around it struck the sheets of rain and glared back into my eyes.

Then I saw the bank. It was steep and overhung with vines and great shiny leaves, and muddy slope that was bleeding rivulets of red, laderite soil into the Kasai.

“Cinq metres!” I shouted over the din of the torrential rain on the roof.

The captain swung the wheel and the riverboat moved away from the bank until again all I could see was the rain.

For the next hour, I peered through the bead curtain of rain calling out whenever I saw the bank.

Of course it was insanity to be navigating at night in such a storm but it was no longer safe to tie up, either.

I have always liked storms. As a child I liked to go up into the mountains when the wild summer storms came, and stand in the wind and the driving rain with the lightning playing about me. I knew it was dangerous, but being part of the pure, wild power of the elements gave me a sublime sense of exhilaration.

That hour in the wheelhouse, in the tropical rainstorm that drowned out all other sound and washed the air clean was one of the most marvelous I have known.

By midnight, the rain stopped and the spotlight could be fixed to shine on the bank a hundred yards down stream, as our riverboat forged ahead of the dark, oily smooth river on our mutual journey to meet the mighty Congo.

The next day, while I was standing at the railing, watching the coffee-colored river slip by, the eight missionary children who were on board sidled up to me, their faces fixed into expressions of sweet innocence.

“Auntie Lynn, we have something for you,” they said in that devilish singsong of children up to mischief. “Close your eyes and put out your hands.”

I did as they asked and when I opened my eyes there was a giant Hercules beetle occupying most of each palm. They were black with a vertical pincer on the forehead. One rested content in my palm, the other hissed and snapped his pincer at me.

I took them to my cabin. Any pet is better than no pet.

The next morning when I awoke, I found the friendly beetle had snuggled up besides me on the pillow, while the ill-tempered one had betaken himself to the farthest corner of the cabin. He spent the rest of the voyage in the cabin keeping his own unpleasant company, while the other rode around all day on my collar.

I was worried that my pets might be hungry but the captain couldn’t see tying up in a war zone while I harvested heart of palm for two beetles.

We stopped at a fueling station and the passengers lined up along the railing to watch the Congolese carrying wood aboard.

One of the missionaries whose mind had been very troubled the whole voyage, suddenly turned to us.

“The cannibalism in the Kasai is not a failure of the Christian principals we’ve instilled, it’s a matter of protein need. They are fighting a war, so they must have protein. The bodies of their enemies are the only source of protein available,

I thought to myself, the fact that there is a war is a failure to instill the principles of the Prince of Peace. But the Europeans could hardly offer themselves as a better example. To me, cannibalism was not especially horrifying. Once a person has been killed, the disposal of the body is very secondary.

But the cannibalism in the Congo was used as a form of terror as well as a source of food.

In fact, there was soon a wanton waste of human meat, with only the prime cut, the rump roast removed and the rest left to rot. But soon entrepreneurs saw the commercial value of what the warriors left behind, and the government had to pass a law that no meat could be sold in the market without the hide attached.

After a hasty refueling, the riverboat pulled away from the bank where it was so vulnerable.

click to enlarge

click to enlargeThe Kasai River was quite wide but the navigation channel was near the shoreline, and so we had an excellent view of the jungle and the villages as the boat moved along.

In some sections, the river split into many smaller streams through marshy flats, where we could see for miles. Then it came together again between steep jungle banks with gashes cut by the rain.

About every half hour we passed a village set in a clearing. Some villages had nets hung out to dry and dugout canoes, because they were fisher people. Others had great piles of wood in front of them because they made their livelihood selling fuel to the riverboats.

At noon, I went over to the native boat to look around and have a meal from their kitchen (to the horror of the First Class purser). As in most of Africa the food was unspiced with corn meal mush as the staple, as in much of Africa.

We arrived at Banningville the next afternoon. Banningville was an important communications center where the Kasai and Congo Rivers joined. The land was hot and flat, with dense jungles.

The local women carried their burdens in a basket on their backs supported by a strap across the forehead, in the manner of mountain people.

Elsewhere in the flat country of Africa, women balanced their burdens on their heads usually in a white enamel basin covered with a kerchief. But I often saw women walking with empty 20-gallon oil drums balanced on their heads, but how else could one person carry a 20-gallon drum?

Because of their method of carrying, the women of Banningville were bent and graceless, in distinct contrast to the statuesque grace of the other women of the Congo.

click to enlarge

click to enlargeWhile I ate supper, I watched the crew attach still another Third Class boat to our side of our OTRACO riverboat and put even more barges out front. We were now a flotilla!

Among the Europeans who came to the boat to see who was aboard and get the latest gossip from up river, was the young director of Post and Telegraph, Mr. Mathys.

He beautifully handsome and spoke perfect American because he had served for a number of years in the American Merchant Marine.

Having seen the world, he returned to the Congo where he was born and married his sweetheart, who had waited all those years. Now he was chief of Post and Telegraph and the father of three little sons. He was deeply worried about the safety of his wife, who was expecting again, and his children. But he was determined not be driven from his home and the country of his birth by “other Congolese dancing around my house yelling ‘Uhuru’.”

He asked me if I would come out to the house, as his wife got so little company these days.

We ran down the gangplank through a maddening swarm of tiny insects and got into his Volkswagen. On the way out to the house, he tried to hit a civet cat that darted across the road. He already had two skins and needed a third to make a stole for his wife.

Mrs. Mathys was a plain, worn woman in her thirties who looked much older than her youthful husband, but the isolation of the Congo had given her a child-like simplicity. Their three sons were beautiful beyond belief and the couple lavished love on them. Mr. Mathys did not like having his wife alone in the house without servants, but he was afraid to have servants in the house, now.

We talked long into the evening and Mr. Mathys showed me the sketches he had made while at sea and the poems and songs he had written. Then he took me out to see the transmitter which he had assembled mainly from old receiver tubes and chicken wire.

When I left the Mathys family that night, I felt as if I had been in the company of very special people who were too good for this world. Later, I tried to reach them through every possible channel to find out how they came through the troubles after Independence, but it was like dropping pebbles off the edge of the earth.

The riverboat sailed at midnight and there was a last minute rush of people European and African to get aboard.

The next day, the open decks of the Third Class boats were spread with drying fish and the stench was so awful that the Europeans spent a great deal of time one the prow of the first barge, upwind of the fish, instead of lounging besides their cars. But most of the sunlit hours were too hot to go out there and so the stink had to be endured.

The barge tops were classless territory, shared by the natives and the Europeans, and both groups amused themselves by noting the peculiarities of the other as we sailed through vast stretches of swamp, broad miles of flat, barren land, and finally hills that looked rather like Wales, on our way down the great Congo River to Leopoldville.

-------------------------------- End of Kasai River section-----------------------

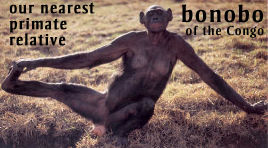

click for page about bonobos

click for page about bonobos

click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge