THE MOVIE COMPOSER AS A DRAMATIST

from the Movie Maestro Trilogy, Book I, by D'Lynn Waldron ©2002

“Where are we going?”

“To see Teen Slasher III.”

“You must be kidding!”

“Movie music is a kind of language that talks to the audience. That language has been evolving since the days of the piano in the pit of the silent screen theatres. Every genre, including teen horror, has its own version of the syntax and vocabulary. Great movie composers help refine the syntax and add to the vocabulary, so that communication with the audience keeps getting better.”

“What about all those pop songs in the score?”

“The teen audience expects that. The songs will initiate and I will elaborate. Despite how I may talk about a picture like this, I always do the best I can, and I can help TerrorVision.”

“How?”

“A good composer of movie music is as much a dramatist as the screen writer. The music should help the dramatic development of the film by evoking emotions in the audience, by explaining the inner feelings of the characters, and by pointing out what is important. Music can prepare the audience for what will happen, or recapitulate what has happened, or deliberately mislead the audience to set them up for a shock. Horror flics make use of that. The music can emphasize that a comedy is a retro homage by using judicious mickey-mouse hits. Music can be a link between related scenes in a movie, and bridge scenes. Music can orient the audience in time and place, which can be very important in films that move about in time and place and/or use flashbacks.”

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

THE MOVIE COMPOSER AS A SCHOLAR

from the Ariane Trilogy, Book I, by D'Lynn Waldron ©2002

Marsh was in the digital studio and sampling instruments from the DVD of Quo Vadis in preparation for his Spartacus score.

“Are you using Miklos Rozsa music?”

“Composers build upon each other’s work, just as you scientists do. Miklos Rozsa was a scholarly musicologist and for Quo Vadis he got instruments as close to the Roman originals as possible. There are no examples of Roman music, so he researched the ancient Greek and Hebrew music on which it would have been based.”

“How will you use what he did for Quo Vadis?”

“I’ll use his instruments for ‘color’, just as I’d use bagpipes for Scotland. I’ll also be drawing upon the historic melody lines, though in Spartacus that isn’t necessary to orient the audience to time and place, as I had to when I scored that movie about Hemingway in 1920’s Paris, 1930’s Africa, and 1940’s Cuba, all in flashbacks. The audience would have been completely disoriented without the music to tell them where they were.”

“Will you listen to Alex North’s score for the Kirk Douglas Spartacus?

“I’ll try not to even remember it. It’s too easy to be influenced without realizing it.”

“Your music has to convey the primal emotions driving Spartacus. We’ll go to the library and study writings by other slaves who have rebelled.”

“Maybe the final battle could be seen from both the deluded heroic view of Spartacus and from the reality of his followers being slaughtered by the Roman legions.’

“Maybe at the end it could be music without sound effects like the battle in Kirosawa’s Ran.”

“I can suggest, but others decide Too often I have to please so many different people that the music ends up in the mediocre middle.”

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A MOVIE PREMIERE: THE COMPOSER ISN'T A CELEBRITY

from the Ariane Trilogy, Book I, by D'Lynn Waldron ©2002

Marsh and Ariane got into a limousine that the studio had sent for them. Not one of those awesome stretch limos, but an ordinary black sedan with dark windows.

“Don’t feel bad, they send motor scooters for screenwriters. They didn’t invite the writers at all until the Writers Guild made that part of their strike demands in 2001.”

“What if Shakespeare were alive?”

“If he weren’t so long dead he couldn’t get a job- ‘screenwriters over fifty and under four-hundred need not apply’.”

“They don’t feel that way about movie composers.”

“Most of my movie albums are bought by 16 to 24 year olds, and they’d hire Methuselah if he had that demographic. Many movie composers working today are in their seventies and eighties. I’m aiming for at least one hundred.”

"They don't put your name on the cover of your soundtrack CDs, just the stars and director. At best, your name is on the back in the tiniest possible print below the tracks list, and sometimes it isn't even there, but lost somewhere in the liner notes."

"What sells my CDs is the movie's title and the pictures of the stars. The only place I care about seeing my name is on the royalty check."

It took an hour in the jam of evening traffic to get to newly restored Egyptian Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard.

They joined the line of limos waiting to discharge their celebrity passengers at the red carpet.

Blue-white searchlight beams were rotating around in the night sky and they could hear the shrieks of the fans as the movie stars went in.

As their car approached the red carpet that went up into the forecourt, they could see the blinding halogen lights of the TV cameras in a solid line behind a rope along the left side of the red carpet, while the station’s interviewers scurried up and down on the red carpet trying to get stars in front of their camera for interviews.

A mob of paparazzi were jostling each other on the sidewalk behind a barrier, and on the sidewalk across the street, a crowd of highly energized fans were jumping up and down for a better view.

Marsh helped Ariane out of their limousine and they started up the red carpet.

The fans shrieked like banshees and the TV interviewers rushed towards them, and right by them to interview the glamorous young couple who got out of the limo behind theirs.

Not a single fan, paparazzo, or interviewer paid any attention to Marsh and Ariane as they walked quickly up the red carpet and into the theatre lobby.

As they made their way across the lobby towards the doors into the theatre, Ariane saw a table with big bags of popcorn and 24 ounce soft drinks with straws sticking out of the lids. She grabbed one of each and put them into Marsh’s hands before he could protest, and then she took one of each for herself.

“I don’t want this stuff.”

“It’s a three hour movie; I’ll need two bags of popcorn.”

As they went in through the doors, a studio wrangler pointed them to two aisle seats with Marsh’s name on an 8 x 10 sheet of paper taped to them.

Marsh only stayed seated until the wrangler’s back turned, then got up and said to the people seated around him, “Give these seats to someone from BAFTA who was put too far front.” And he slipped furtively out into the aisle followed by a puzzled Ariane.

Marsh led the way up the aisle and over to darkened stairs at the side.

Ariane followed Marsh up several flights and they emerged at the top of the balcony. Marsh went down to the front row of the mezzanine seats, and sat in the middle.

“These are the most expensive seats in a British theatre. They’re the only place to see a ballet properly, and in the movies you are looking straight ahead at the screen with nothing in front of you. And I have to keep far away from those speakers on the floor behind the screen with their blasts of sound; they can deafen me with my own music!”

The house lights went down and the movie started.

The 'Tempest' began with a beautiful overture and stunning images which the audience applauded because the production designer Rick Heinrichs and the composer were both in the audience.

After the movie, as Marsh and Ariane walked back down the red carpet, one of the dozen security guards dressed in black suits with badges who were stationed around the forecourt, pointed in the opposite direction from the parking lot where their limo was waiting.

“Party’s around the corner, down one block, turn to your right, then turn to your left. We have people all along the way. Watch out for the broken sidewalks.”

“If you want to go to the party, we will,” Marsh offered in tones of self-sacrifice.

“Don’t they expect you?”

“Nobody will notice if I'm not there. The producer and director devoted four years of their lives and risked their careers on this project. The cast, crew and technical people bonded during three months of very difficult filming on a Greek island. I only came in after the film was in rough cut. I worked alone in my studio for a month, then flew to London to record the score. This is the third major movie I’ve done this year, so I don’t have the same emotional involvement as the others do. But it will be different with Spartacus because I’ll be one of the team all through production. My Yorkshire Philharmonic was a team and I miss that.”

Just then the elderly knighted British actor who played Prospero came by on his way back and said in his famed stentorian tones to those waiting to start out on the trek, “Lousy party.”

“OK, Marsh, we go home. When an actor says it’s a lousy party, that means the food is no good.”

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

TEMP TRACK HELL

from the Ariane Trilogy, Book I, by D'Lynn Waldron ©2002

Marsh read his e-mail and groaned.

“I was supposed to have complete artistic on Mind Games. Now they want my music to sound like their temp track.”

“What’s a temp track?”

“What I listen to only if the director can't express what he wants any other way. To create a temp track the music editor pastes together pieces of music to be used with the preliminary edits of the film. These edits are shown to the producer and to preview audiences. Unfortunately, if the producer or director falls in love with the temp track, or if they get a good response from the preview audience, they want the composer to just rip-off the temp track. If these Mind Games people stay married to the temp track, I walk. I wouldn’t do a rip off of someone else’s music even if were Bach, and believe me this isn’t Bach!”

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A SCORE GETS BUTCHERED IN THE PRODUCER'S CUT

from the Ariane Trilogy, Book I, by D'Lynn Waldron ©2002

“Why aren’t you going to the premiere of Laramie tonight?”

“The same reason I will never work for that production company again. After the director’s cut, the producer and a bunch of studio executives recut the movie. They chopped my cues into bits and pieces and stuck them in places they were never intended to go, and they tracked in cues taken from other movies the studio has done. They've turned my music into a personal embarrassment, the worst part of which is that people will recognize those tracked cues from the other movies and think I just plagiarized someone else’s music because I ran out of ideas.”

“When the album was released this week it got very favorable reviews on 'Film Score Monthly'.”

“Because I was in total control of the album. Anyone who goes to the movie to hear the music the way it is in the album is going to be very disappointed.”

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

GETTING GIGS

from the Ariane Trilogy, Book I, by D'Lynn Waldron ©2002

They were at the long PCH light at the bottom of the California Incline and Marsh took a call from his agent Joe on the hands-free cell phone.

“Do you want to do the last minute rewrite of the Earthquest score?”

“I looked at the assembly. A score by Mozart couldn’t save that stinker.”

“Is it ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ on a Boston Pops guest appearance next spring?”

“Can't say yet. Depends on my schedule.”

“The Hollywood Bowl tribute concert with film clips in August?”

“OK to that.”

“Monaco wants to award you the order of something or other, but of course you have to go there and conduct a benefit concert to collect it.”

“Too busy. Offer them Jeff and his fiddle; he needs gongs for his jacket.”

“How about a quick twenty-thousand dollars for a package deal to do twenty minutes of synth underscore to go with the pop songs in the spy pic Mind Games.”

“I’ll hold my nose and compose.”

“Their music editor needs your tracks Friday to do the final music edit. They start dubbing Monday. They’ll satellite a QuickTime locked cut with a predub of the voice and sound tracks, a track with the actual songs they’re using, and their temp track. The music editor has already done the spotting sheet. I’ve got their check for ten thousand and a satisfactory deal memo. Our lawyer will do the long form contract Monday.”

“Get that check to the bank. I want it cleared before I deliver the master. This is an indi company. The composer works last, so it’s always the composer who doesn’t get paid when the money runs out.”

“I assume you do not want screen credit.”

“You assume right.”

Marsh switched off the satellite phone.

“How can you do a film score in seven days?”

“It will take me less than twenty hours. I’ll just compose at the electronic keyboard while watching the movie on the monitor with the predub and the pop songs they’re using; I always ignor the temp track. Then I’ll transmit the electronic master file to the music editor and I’m finished.”

“What about the Galaxy II music for Toronto?”

“I have ten days to do five minutes of composing and orchestration before it has to go off to the music contractor to prepare for the recording session with the symphony. I can do from ninety seconds to two minutes of fully orchestrated score a day. Of course I like to have weeks to consider what that should be, but I very rarely do. Sometimes I get a reshot scene in the afternoon and the cue has to be to the music editor in the morning!”

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

HOW MOVIE COMPOSERS SHOULD BE ALLOWED TO WORK

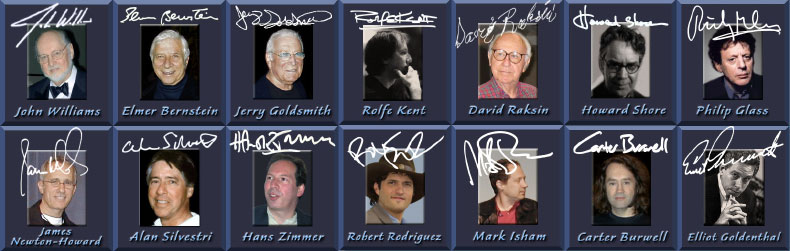

from the Ariane Trilogy, Book I, by D'Lynn Waldron ©2002 (with thanks to Elmer Bernstein for his wit and wisdom on this subject)

Marsh set up two microphones for his conversation with Ariane that would be the composer’s commentary track for the Special Edition DVD of FantasyLand. They began with an introduction that went under the titles.

“What is FantasyLand about?”

“FantasyLand is about an 11 year old Walter Mitty who daydreams stories to escape the realities of life in a Black ghetto. The score turned out very well because of the relationship I had with the director.”

“How did you get the job?”

“The director heard the music I had done for a low budget war movie. He didn’t ask me to do a demo CD of music for a child’s fantasy. He liked the quality of my work and trusted that I could do a good job in a different genre. It was an independent film so he could make that decision. He didn’t have to get the approval of the seven dwarfs in the front office or the suits in New York.”

“What was the process of composing?”

“I met with the director and we discussed the movie and his ideas for the visual and emotional content. By the end of the meeting, we knew we could work well together. He gave me the script and said to come back in two months.”

“Then what did you do?”

“I had time to dream with that boy, to go out and walk around the neighborhoods he would have lived in, and talk with the people who would have been his family and neighbors. I went to schools with the permission of the principal, and watched and listened in the playgrounds and lunch rooms, and talked with the kids about their daydreams. The director gave me the time and artistic space to create the themes for a coherent, meaningful suite of music. You can’t do good work when you have to crank out a cue every few days for the approval of a director who micromanages your music note by note.”

“What came next?”

“I played five themes for the director on the piano. He liked four of them including the 'High Flight Theme'. He asked me to compose some of the music and mock it up on a synth before he began filming so the scenes could be choreographed to the music like a ballet. For the rest of the score we worked together while he was editing. Sometimes he edited a scene to fit my music and sometimes I wrote the music to fit his cut.”

“Was there ever a temp track?”

“Not the horrible kind that's cobbled together from bits and pieces of unrelated music and used for the previews. Instead, the director of FantasyLand squeezed the money out of the budget for me to take my score to China where musicians from their symphony orchestras can be hired inexpensively. I put together a twelve piece orchestra and did a temp track based on the music I had written for the film”

“And then?”

“The director, the editor and I used that temp track of music I had composed for the film to see what worked and didn’t work in the scenes before I did the final score for a full symphony orchestra. And that temp track was also used at the previews so the front office Munchkins wouldn’t want a good scene changed when it didn’t work because of a bad temp track.”

“And of course you won the Oscar for FantasyLand. Do you often get to work that way?”

“Only one other time- on the first Galaxy movie. Milt, our producer, trusted me completely. It began as an independent production and my score was recorded before the movie was picked up by a media conglomerate. They wanted to replace my score with a work-for hire-composer because I was to get both publisher and composer royalties and they wanted all the royalties for themselves. Milt stood up for my music and it was too late in production for the front office Munchkins to impose their opinions on my score.”

“And that was your second Oscar.”

“When they let the composer compose they can get a good score, and sometimes a great score. But that’s impossible when the composer has to crank out music in bits and pieces every few days for piecemeal approval by people who know nothing about music. That didn’t used to be the way scores were done, and it shouldn’t be the way they’re done now.”

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

SCORING A VIDEO GAME

from the Ariane Trilogy, Book I, by D'Lynn Waldron ©2002

Ariane came in through the kitchen door and dropped her briefcase on the table.

From the bedroom she could hear what were the unmistakable sounds of an outer space shoot-em-up video game.

Ariane hurried up to the bedroom expecting to see a child, but there was Marsh sitting in the middle of the bed in front of the plasma screen video with a computer game control in his hands, trying to protect his spaceships, which were being blow up all over the screen.

“This is work!”

“So why are you doing it?”

“A computer game company has licensed the Galaxy movies and they’ve hired me to do the cinematic music that’s used in the advertising and for the exposition, which is a mini-movie before the game starts. The producer knows nothing about music, but he's popping for a 90 piece symphony orchestra because that’s what Spielberg had for the ‘Medal of Honor’ game.”

“Why don’t they just use the soundtrack?”

“They can’t afford the licensing fee, so I’ll compose similar sounding music for their game. That’s done all the time by game composers, but the company wants to use my name on the box.”

“Use your name?! They don’t even put your name on the front of your soundtrack CDs.”

“Believe it or not, game fans are very aware of the music, have fan sites for the composers, and buy game music on CDs. This game is coming out on five CDs with Dolby 5.1 surround.”

Ariane took the control from Marsh and her spaceships were blown up even faster than his had been.

“How do kids manage to play these games? Look at that, all my spaceships have been blown up, ‘Game Over’.” Ariane said in complete frustration.

“Let me try again. I’m sure it just takes practice. I was very good a Tetris, and I got to the highest level of Lemmings.”

“These games are definitely a boy-thing, so I will leave you to it while I write my comments on this afternoon’s seminar papers.”

At seven o’clock, spaceships were still being blown up in the bedroom.

“Marsh, what about supper?”

“Put something in the microwave and bring it up here. I’m beginning to get the hang of this.”

At eleven o’clock, Ariane finished writing her comments on the seminar papers and went up to the bedroom.

Marsh’s supper was beside him on the bed barely touched, and his spaceships were now surviving and fighting back.

“Turn that thing off, it’s time for bed.”

“Yeh, yeh... just one more game. My last score was over 10,000.”

Ariane tugged the control out of his hands, turned the set off, put the control in her night table and closed the draw. Marsh’s lower lip went out in a pout at having his toy taken away.

The next morning, Ariane was awakened at seven o’clock by astronauts shooting space monsters. Marsh had gotten the control out of the night table draw.

“At least turn off the sound!”

“I need the sound so I can compose the music to go with it.”

“In that case, get out of the bed and go down to the studio with that thing and compose, because I want to sleep.”

“It’s my bed,” Marsh mumbled like a miffed little boy, as he got up and headed downstairs with his game control.

At breakfast, Ariane had some questions.

“If you’re just doing music for the exposition mini-movie, why are you learning to play computer games? They’re just for kids.”

“Games are the largest segment of the entertainment industry, and the target demographic for these action games is men in their late twenties. In the early days, the music and effects were all done by one kid with a synth, now they have a composer, a sound effects person and a sound designer.”

“But why should you learn to play games?”

“To try to get the whole gig. There are three kinds of music in a game. First, the cinematic for the exposition. Second, the shell music that goes under the menus. Third the interactive music and sound effects that are generated on the fly to suit the play.”

“And what kind of music is used for the game play?”

“The music segments can be specific to a setting, to a character, or to an action. Because the music is randomly linked, there must be a seamless fit between related segments. Because the music is repeated many times in different combinations, a melody line can get very irritating so percussion is better for action. And you can’t go over the top the way you can in a movie in which a section of music is used only once.”

“Then it’s a whole new musical genre.”

“Exactly. And the producers don’t know enough to interfere, so it’s a chance to be really innovative. And one thing I really like is that the sound content of the game is planned collaboratively in a spotting session with the composer, the sound man and the sound designer who does the final mix. and then they work together on the whole process.”

“Well, you’ll certainly need a lot of collaboration!”

“Milt’s 12 year old nephew is on his way over.”

“And why are you going through all this?”

“The challenge. And the money. There’s 90 minutes of music and they pay $1000 a minute.”

Ariane jumped up from the breakfast table and headed for the kitchen door.

“Where are you going?”

“To Blockbuster to rent all the latest games!”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

THE DIFFERENCE IN HOW MUSIC IS USED IN THEATRES AND ON CDS

from the Ariane Trilogy, Book I, by D'Lynn Waldron ©2002

When Marsh and Ariane got to the multiplex on the Promenade at Arizona, there were only teenagers in the a long line waiting to buy tickets for Teen Slasher III.

“Why don’t we just rent the DVD of Teen Slasher II?”

“A DVD wouldn’t tell me how they handle the surround sound speakers in a theatre for this kind of movie.”

They reached the window and Marsh asked for two tickets.

“Are you sure you want Teen Slasher?”

“He has arrested development.”

The young man at the window laughed with them and handed over the tickets, still shaking his head. As they were about to walk away from the window, the young man recognized Marsh, and pushed a piece of paper and pen out on the tray.

“Please, may I have your autograph? I’m studying music.”

“My pleasure. Good luck with your studies.”

They went into the lobby and Ariane started to veer off towards the popcorn stand, but Marsh held her firmly by the arm to put her ahead of him on the escalator.

They went into the theatre and sat down at the back and Marsh pointed to the screen.

“Behind the screen are left, center and right speakers, and behind them is a huge subwoofer. Up there around the walls are the surround sound speakers, in this case, four on each side, and two in the back.”

“Doesn’t that make it awfully complicated to mix the sound?”

“It certainly does. There has to be a track for each of the speakers. The center speaker is where most of the dialogue comes from, and the left and right speakers are the stereo music, for which I create two tracks from as many as twelve tracks made by mikes over the various instrument sections of the orchestra, plus additional tracks for any synth or other sources. Pro Tools can handle sixteen tracks at the same time. To mix good stereo you must get a separation between the speakers without the sound becoming lopsided, or overly panned so it goes back and forth like a tennis match.”

“What about the surround speakers?”

“In the theatre, the side and back speakers are mostly used for sound effects. For the home surround music CDs, I take the left and right theatre tracks and make additional tracks using a signal processor to create delays and reverbs, so it will seem as if the sound is coming from the other directions.”

As the theatre darkened, Marsh gave Ariane a pair of the industrial strength ear plugs he always kept in his pocket.

“These kids are permanently hearing impaired from years of listening to music that’s too loud, and it’s very sad because there is a whole beautiful spectrum of sound within music that they will never hear again.”

“OSHA would shut down a factory that had one fourth the sound level of these theatres.”

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

FIGHTING FOR ROYALTIES AND COPYRIGHTS

from the Ariane Trilogy, Book I, by D'Lynn Waldron ©2002

Marsh was in his office on the speaker phone with the corporate accounting in New York.

“Is that rain? Or are you pissing on me?”

“Our accountants have gone over the books and we don’t owe you anything on your backend points on the Galaxy I album.”

“I should never have taken back end, because that’s where I’m getting it!”

“The Galaxy I album has not yet shown a profit.”

“Not shown a profit?! It went double platinum the first year and has been on the charts ever since.”

“There are expenses that our accountants must deduct before there is a net profit.”

“Your accountants could steal a hot stove with their bare hands and not get a blister! I’m sending in my own accountants.”

“Your contract doesn’t allow for that.”

“But my contract does make me the sole publisher, therefore I own 100% of the copyrights to the Galaxy music, so I can and will stop you from using a single note of my music in Galaxy III!”

“I will speak to the CFO and see if some adjustment can be made in our accounting methods for your Galaxy albums. But for us to do that, you will have to sign a confidentiality agreement.”

Marsh hung up without saying good bye. He planted his feet wide apart, punched his fist victoriously in the air

“I won! The sharks in New York have to cough up some of the money they owe me on the Galaxy I album.”

“Why now?”

“Because I own the copyrights.”

“I don’t understand- doesn’t the composer always own the copyright?”

“In music, before something is published, the composer has an automatic copyright on it as his creation. After it is offered for sale to the public, the entity that sells it becomes the de facto publisher and gets to file for the formal copyright.”

“It’s better to write books.”

“Before a piece of music has been published, the composer has to be asked permission for it to be used. Once it has been published it comes under ‘compulsory mechanical license’ and anyone can use it if they pay the standard royalty as established by the Copyright Royalty Tribunal appointed by the President.

“How much is the royalty?”

“For songs with lyrics the royalty is about 7¢ per unit sold. Instrumental music is paid for by the time. With my movie score albums, I get 5% of the list price as composer, and if I am the publisher I get another 5%. That’s a total of $1.50 on a $15 list price album. I also try to get points on the gross profit the album makes.”

“If anyone can use your music under the compulsory mechanical license, how can you stop the Galaxy producers from using your music and just handing you the royalty?”

“No one can use your music as part of a movie, commercial, or anything else that requires it to be synchronized to an image, unless you give them a sync license. Only the publisher can grant a sync license, and the composer can’t veto it. But I am the publisher, so I can refuse to grant a sync license for my music in Galaxy III.”

“How do you get to be publisher?”

“There are three kinds of contracts when you compose music for movies. With ‘work for hire’ you are an employee and the production company owns everything you produce.”

“And the other kinds of contract?”

"There’s a ‘package deal’ in which the composer agrees to cover all expenses for a pre-agreed amount of money. Except for an all synth score I never agree to a package deal because the expenses are always more than you expect, especially if you have to make a lot of changes, or they decide they want additional live instruments you haven’t budgeted for. The composer can easily lose money on a package deal."

"But a package deal was OK for Mind Games because that’s an all synth score?"

“Right. The third way to write for the movies is ‘independent contractor’ which is what I fight for on a major movie because I own my compositions and just license them for that movie, Even with an independent contractor deal, the producers want a minimum of 50% of the publisher royalties, which means 25% of the total royalties.”

“How did you get everything with Galaxy I?”

“Galaxy I started out as a low budget package put together by my friend Milt, an independent producer. In exchange for a minimal fee up front, he gave me an ‘independent contractor’ deal. When a big conglomerate financed the picture, they wanted to replace me with a work-for-hire composer. But Milt wanted my music and to help him grease his deal, I settled for points on net on the album- thus the fight you just heard. According to the sharks in corporate accounting, nothing to do with the Galaxy franchise has ever shown a profit. They cheat Milt too and he hates them as much as I do.”

“What about that uncredited teen slasher movie you did last year?”

“That was work for hire. My underscore was worthless for anything else and the movie album was just the pop songs they licensed. But my name is on the cue sheet that goes to BMI and I’ll get royalties for the underscore whenever the film or music is broadcast.”

“Cue sheet?”

“The list of every element of music, how long it’s used, a reference name for it, and who wrote it and who published it. That’s how BMI knows where to send the royalties they collect.”

“What is BMI?”

“You register your piece of music with an organization that keeps track of when it's used and collects your royalties and sends them to you.

“If I compose the score for a TV show, do I get royalties on that?”

“Indeed you do. Register yourself with BMI both as the composer and with a company name as the publisher and then just make sure the producer sends a Music Cue Sheet to BMI. Every time that show is broadcast BMI sends you money. Don’t go with ASCAP- they only pay if they happen to catch your show in a ‘survey’ and they almost never survey cable, so they ignore the cue sheet sent by the cable network along with the check to pay you, and you can't get your money.”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

HOW MOVIE COMPOSERS WORK WITH THE NEW DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY

from the Ariane Trilogy, Book I, by D'Lynn Waldron ©2002

“Now I vary the melody I composed yesterday so it expresses the different moods within the scene. I always do this on the piano, because on the synth it’s too easy just to hit the repeat button, rather than play the phrase again and make it a bit different each time.”

Marsh spent over two hours at the piano, then he stopped to stretch.

“This afternoon, after my nap, I’ll use the synthesizer to create a sketch with the instrumentation colors and textures. I’ll transmit that mock-up file to the music editor, director, and producer. Often, the hardest thing I do is convince the director to let me do a good score. After that, getting a sign-off on the synth version can be difficult because producers and directors can’t envision how the music will sound with an orchestra.”

“What if each of those people want something different?”

“Usually the director has the final word, but with franchises like Galaxy and James Bond, where there’s a different director for each movie, the producer has the final say so that the elements in the franchise are kept consistent. Fortunately, Milt, the Galaxy producer trusts me completely.

“What do you do after you get an approval on a mock-up?”

“I create a synth version of the full orchestration which I synchronize to the scenes with a sequencer. I have to be careful not to do something electronically that musicians and real instruments can’t do. And I have to remember that a live orchestra, especially a large one, will soften and blend things that are sharp and distinct in the synth version.”

“Then I suppose that has to be approved?”

“And after it is, I generate the notation of the parts using Erato software, but then I have to refine the phrasing manually because automated notation is too mechanical. It’s to get the emotional phrasing that they pay for live musicians.”

“And then?”

“I transmit the digital file of the orchestra parts and the synth file, along with a wish list of musicians I’d like, to the music editor, who gives it to the music contractor who books the recording studio, hires the musicians, and prints the parts.”

“And then you conduct the live orchestra?”

“No. First use Auricle software to add clicks and streamers to the scenes they project while I’m conducting so I get the timing exact. That’s very important with a symphony orchestra because they tend to be a bit behind the beat.”

“And once the music is recorded, you’re finished.”

“No! I won’t let anyone else orchestrate or conduct my music, and now that I can do it in my studio with Pro Tools, I also mix the tracks from the studio mikes and the synth into the stereo master file that’s dubbed into the film, and used on the CD, if the CD isn’t recorded separately.”

“And then you’re finished!”

“Not if it’s a score I care about! If there isn't a competent Sound Designer on the production, I have to go to the dubbing sessions where the editor puts all the sound tracks together, so I can defend my music against dialogue editor who wants to make it so soft it’s wallpaper, and against the sound editor who wants to drown it out with his effects. Now things can be really bad on low budget productions because they sometimes use the dialogue editor to also edit the music. Directors used to know how to create emotions with images and music. Movies today use blasts of sound to get a reaction from the audience. Composers like Herrmann were allowed to do a narrative score that told the story in music. Today, they use a mishmash of unrelated pop songs to sell on a CD.”

“Creating movie music is a complicated process!”

“Not always. I’ve done all-synth scores where I’m sent the final cut, write the score, transmit the stereo master, and never hear from anyone. I hope Mind Games will be like that, because on their budget they’re not entitled to have opinions!”

“How much music do you have to write for a movie?”

“Depends. Some two hour movies should have only 20 minutes of score. Some need wall to wall music. The Galaxy movies have a lot of scenes that are just space ships and mechanical creatures at war. Scenes like that must have music to involve the audience’s emotions. Galaxy II is 120 minutes and will have 100 minutes of original underscore that are in about 40 separate pieces called cues. Cues can be from a few seconds in one scene, to many minutes extending across several scenes. There’s also the main title music, which is a proper composition, and the melody for a song that will go under the end credits to be cross-promoted with the movie.”

“What about the album?”

“The last thing I do is create the suite for the CD, which is very different from the way the music was used in the movie. And the suite sometimes contains additional music that isn’t in the film because that scene was cut. My Galaxy CDs are such big money makers that they let me record the suite separately. With a lot of movies I have to paste the suite together from what was recorded for the sound track.”

“What happens to music that isn’t used in the movie or album?”

“Sometimes they have me rewrite a cue half a dozen times, or even rewrite the entire score when the movie doesn’t work and they hope that will fix it. I don’t get paid extra for redoing music, but they think they should own everything I wrote. My contracts specify that all rights to music they don’t use revert to me.”

“How many cues do you have left to do for Galaxy II?”

“Four major cues; about five minutes of music. Two new love scenes; one romantic and one passionate, and two new effects scenes; a time warp into a black hole, and a spaceship battle, which the effects houses are still working on. I have a rough cut of the romantic scene, and they’re filming the passionate scene Monday.”

“How can you synchronize music to scenes you don’t have?“

“I’m creating everything I can in a synth file that can be digitally stretched and compressed at the recording session- the director always wants to tweak the timing anyway as he looks at the film while the music is being played at the session. The musicians have to be able to make those changes without rehearsing, which is harder with a symphony orchestra than with a handful of sight-reading session musicians. With session musicians I can even improvise, if the director wants something entirely different after he sees the music and the movie together while we’re recording.”

“What sort of things do you put in that synth file?”

“Extra percussion and weird instruments that I have as digital samples- I’m taking at least 30 synth tracks to Toronto for just these four cues.”

“Aren’t you under terrible pressure doing things at the last minute?”

“If you can’t take the pressure, you can’t be in the business. Major movies are often mixed a week before the premiere, and usually the composer isn’t called in until the very end. I’ve done synth scores where I was transmitting cues every night for a week that would be dubbed the next day.”

“I couldn’t work like that!”

“No composer wants to work under extreme pressure, but some composers like Danny Elfman don’t want to be brought in until they can see something near the final cut and have a gut reaction to the entirety of the movie, which can be very different from the script and rushes. Hans Zimmer liked being in from the beginning of the creative process with Gladiator and when they were filming on location, Zimmer composed music to which the director 'choreographed' action scenes. When James Newton-Howard does a Disney animated movie, he demos the main themes at the very beginning of production and then whole process through final animation takes five years!”

“Which would you prefer?

“Some movies I like to do one way, and some the other. I wouldn’t want to be part of the ‘creative process’ for Mind Games. And if a movie is going to be seven years in development hell, then three years in preproduction, of course I don’t want to suffer through that, but Stan has the studio’s greenlight for Spartacus, and it would be great to work on it from the beginning.”

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A SPOTTING SESSION

from the Ariane Trilogy, Book I, by D'Lynn Waldron ©2002

After they watched the cut of TerrorVision on a DVD, Marsh said philosophically. “Well it could be worse,”

“How?”

“The songs on the temp track are very good of their kind. Let’s hope they’ve negotiated affordable license fees and they don’t run out of money before they’ve paid for them.”

At ten minutes of ten they drove into the parking lot of the long two story building on the south side of Olympic at 30th.

The building had a row of production company offices facing the street and they went into the Todd AO part of the building, which had a beautiful three story atrium lobby with tall tropical plants and water bubbling over natural stones.

They went down the flight of wide steps to the lower level. On their right, Ariane saw the open kitchen area with platters of food from a breakfast buffet. She nipped over and grabbed a bagel with cream cheese and lox, and two skewers of fresh pineapple.

Marsh continued down the short hall to the inconspicuous, recessed, screening room door on the right and waited for Ariane to catch up. Before going in, he took a big bite of her bagel.

The screening room could seat about sixty people, and three rows down from the projection booth, in the middle of the row, was a console with built in controls and two telephones.

The music editor and the director were already sitting on the far side of the console. The director was about twenty-five and wearing the obligatory baseball cap, deliberately grunged up so it would look as if he had made many other movies.

The music editor was an African-American about twenty.

“It’s an honor to meet you, Sir Marshall. I went one year to Juilliard, but last year I got a gig with MTV and the money was so good it was good-bye Mozart.”

“You made an excellent choice of pop songs.”

“Thank you, but they had to be chosen for the movie album, not the dramatic needs of the picture, which is why I told the producer we had to get someone of your caliber to do the underscore.”

Marsh sat down on the near side of the console and Ariane sat down next to him. She sunk into the soft cushions and found that the seat could be tipped back to a very comfortable angle. No wonder Marsh liked this screening room.

Ariane was worried that the half bagel and two skewers of pineapple was all she the food she would see until they left, but the director’s assistant handed out the first of what would be a steady supply of cafe latte’s and excellent sandwiches coming from the restaurant in the complex.

The music editor handed out sheets titled ‘Music Spotting Notes’ which already had the reel numbers, cue times, and reference names for the cues filled in.

The director turned to Marsh.

“There are several scenes that have to be fixed in the mix.”

“I can help, but I can’t replace with music what isn’t on the screen.”

The director phoned up to the booth and the projectionist ran the first of the digital clips with SMPTE time code.

The clip was kids running out of school at the start of summer vacation.

“I see it as brio,” the music editor said to Marsh.

“A pot scrubber...?” the young director asked offended.

“Light, sparkling, full of fun, school’s out, wheee!” Marsh explained.

“That’s it!” the director said happily.

For each cue they discussed the kind of music and the instrumentation, then second by second in the cue where the music should start, where it should stop, fades, and cross-fades, and finally they decided the exact frames on which the hits should come.

The young director repeatedly overrode Marsh’s suggestions, even when the music editor tried to support Marsh.

Marsh whispered to Ariane, “I’ll just agree with whatever the director says, then do it the way it should be done. He’ll never know the difference and the music editor certainly isn’t going to tell him.”

At one o’clock, Marsh’s agent, Joe, came in with the check and spoke very loudly for everyone to hear.

“Sir Marshall, here’s your check from three hundred and thirty thousand dollars of your million dollar fee for Spartacus.”

The director and music editor were in total shock, both at what Marsh was getting for Spartacus, and what they had gotten him for.

For the rest of the spotting session, the director did not make a single change to what Marsh suggested, and at the end he bowed low over Marsh’s hand as he shook it.

“Sir Marshall, don’t worry about anything we said earlier, you do whatever you think is best. We leave it entirely to your judgment.”

When Marsh and Ariane got back in the car, they both started laughing.

“I should have Joe bring a copy of that check to me at every spotting session!”

------------------------------------------------------------------

OSCAR POLITICS

from the Ariane Trilogy, Book I, by D'Lynn Waldron ©2002

“What do you have to do today?”

“See about a gig. It’s another disaster in the art of film making, but it will gross hundreds of millions at the box office.”

“What’s it about?”

“I think the earth cracks open and they have to hold it together with bungee cords and bubble gum. Who cares. The money is very good, so once again I will think of my mortgage, hold my nose and compose.”

When they got to Santa Monica, they drove up Montana, across on 11th, then west on Olympic and made a right turn into short, dead end 10th Street.

Both sides of the street were lined with production company headquarters in small buildings that had once been machine shops. They parked and went into one. The floor space was open to the twenty-five foot high ceiling and divided up with eight foot high partitions. On the partitions were posters of the producer’s other disaster, teen terror, and car chase movies.

Ariane sat in the main area across from the large canteen and read ‘the trades’ that were on the coffee table, while Marsh was in the producer’s office.

When Marsh came out an hour later, he looked somewhat optimistic.

“Good news and bad news. Gross participation in the album, but the picture is only ‘in development’, not greenlighted, so even if it does materialize it will be several years before I get the work.”

“I read that the typical movie that actually gets made is eight years in development, and for every movie that gets made, a hundred are stuck in development hell forever.”

“While their previously bankable action star goes into the ‘terrible twos’- too old and too fat.”

They went down Olympic to Fifth and turned north on their way to Ariane’s grandmother’s.

“When we get back to Malibu, we’re going to rent that supernatural shtick flick Demons from Above. It’s studio is putting real muscle behind it for Best Original Score while trying eliminate my Good Solider score.”

“How can they eliminate you?”

“The 250 members of the Music Branch vote for five nominees, then the six thousand members of the Academy vote for the winner. The Music Branch has a rule book that says the lyrics of the song must be clearly audible in the movie proper and must contribute to the dramatic development of the story. The rule book also says that the major elements of an underscore must be new and written for that film.

“And?”

“The lyrics of The Good Soldier were added to a melody from my score to be sung under the titles for cross promotion. When the song became a big hit before the movie was in wide release, the studio pasted it into the film proper so it would be eligible for an Oscar.”

“Did that make it eligible?”

“No, because the movie already had a limited engagement.”

“But what’s the problem with your Good Soldier underscore?”

“The melody they used for the lyrics comes from my concerto that won the Young Composer award nearly forty years ago.”

“That melody is only used for a couple of minutes, so it’s hardly a major element.”

“The other studios are arguing that because it’s a hit song and in the movie proper, it is a major element, and therefore my whole underscore should be disqualified.”

“But if the song isn’t eligible because it wasn’t in the initial release, then it being in a later release can’t disqualify your underscore.”

“So my studio is arguing, but I’d rather see Ennio Morricone win, anyway. He’s in his seventies, he’s scored over four hundred films, this is his sixth nomination, and he’s never won an Oscar. He deserves an Oscar, and three won’t get me any more jobs than two. It’s a big thrill when you hear your name called, then a week later you’ve forgotten all about it.”

“I’m glad you’re not hooked on winning, because that's an addiction that destroys people."

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

A SIGNING WITH JULIA CHILD

from the Ariane Trilogy, Book I, by D'Lynn Waldron ©2002

“Kate, we’re going to COSTCO and we’ll be back around five.”

“Get two Foster Farms roast chickens while you’re there.”

Marsh and Ariane arrived at the Marina COSTCO in the Ferrari to find the lot jammed with pre-Christmas shoppers.

“Park way over there at the far end of Albertson’s so we won’t get the door banged.”

“We’ll be OK,” Marsh said and drove right up to the entrance where an employee dropped a rope for him to park next to a limo.

Ariane saw two lines of people, one a short line to one side of the entrance and at the other side of the entrance a line that stretched clear around the building. A big sign in front of the long line said,

PRE-CHRISTMAS COOKBOOK SIGNING BY JULIA CHILD: LINE STARTS HERE.

In front of the shorter line was a sign with a picture of Marsh being presented his Oscar by Julia Roberts.

PRE-CHRISTMAS CD SIGNING BY SIR MARSHALL CHALFONT, COMPOSER OF THE GALAXY AND FANTASYLAND MUSIC: LINE STARTS HERE.

“My record company knew Julia Child would draw a big crowd, so they set me up for the same day.”

At precisely two o’clock Marsh and Julia Child took their places at tables, marking pens at the ready. An assistant stood beside Julia Child to keep her table supplied from the cartons of books on the floor.

Marsh turned to Ariane, “The CDs in the cartons have the wrappers removed so I can sign the liners; just keep plenty of everything on the table.”

The rope was dropped and the lines surged forward.

Julia Child had the infirmities of age expected of a woman who had served in China with the OSS in World War Two, before becoming television’s beloved French Chef and an American icon, but, by God, could she sign books! Ariane clocked her for several minutes and calculated she was signing at a rate of 300 books and hour! Ariane further calculated with a royalty of $3.50 a book, she would earn $2100 for her two hours work.

Marsh didn't have the same amount of traffic at his table, and if he had it would have been a problem, because he talked to each person as he signed their CDs.

When Marsh’s line had thinned out so that there was time between customers, he found himself getting spillover from Julia Child’s line, and pretty soon about a third of her customers were moving on to his table, and having CD’s signed for Christmas gifts.

Among the people who came just for Marsh were two teenage boys, one a short, tough redhead and the other a tall thin African American trying to grow dreadlocks without much success. Both were dressed in baggy clothes, with trousers about to fall off their backsides.

Ariane saw that they were both suppressing giggles of nervous mischief. For a moment she was concerned and got ready to jump between them and Marsh, but then she realized they were just up to some innocent fun.

Each of the boys set a computer recorable CD in a plain jewel case on the table. Clearly written in marker on the CDs was ‘Galaxy Music, MPEG from Napster’.

Marsh looked at the CDs with the pirated music, picked up his pen and signed the jewel cases.

“Can you get Maria Callas recordings?”

“Sure. You can get MPEGs of anything on the internet.”

“I was born too soon. What are your names?”

The boys looked as if they were about to bolt, but his gentle smile reassured them.

“I’m Tommy and he’s Bart.”

Marsh took two FantasyLand CD’s and signed one to ‘Tommy’ and one to ‘Bart’ and handed them to the boys, then signaled to the COSTCO guard- “These are a present from me, so they don’t have to go to the register.”

“Gee, Mr. Chalfont, you’re a really cool guy!”

“Enjoy the music.”

The boys left proud as kings and ten feet tall.

Ariane leaned over and kissed Marsh on the top of the head.

“You really are a cool guy.”

Before they left COSTCO after the signing, Ariane bought the two roast chickens, and as they were getting into their car, they saw Julia Child and her chauffeur pushing a shopping cart with her roast chickens!

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

BROADCAST FOR SCHOOL CHILDREN AND THEIR MUSIC TEACHERS

from the Ariane Trilogy, Book II, by D'Lynn Waldron ©2002

This scene is from Book II after Marsh has lost his fear of losing his dignity.

Marsh led Ariane into the William Holden sound studio on the Sony/Columbia, erstwhile MGM, lot. There was a grand piano on the stage and two television cameras.

The seats in the small theatre were filled with grade school children and their school music teachers.

“Sit here. I have to go change.”

Clarissa Falconi, an elegant, elderly woman with beautifully coifed silver gray hair came on stage.

“How many of you are studying a musical instrument?”

About twenty per cent of the hands went up.

“How many of you want to study an instrument?”

All the hands went up,

“Sir Marshall Chalfont and the Women’s Committee of the Youth Symphony have set up a fund to buy instruments for the schools.”

The music teachers applauded vigorously.

“Now I would like you to meet my new student.”

Marsh came out with his midnight blue dress trousers rolled up above his knees, high white socks, a French navy jumper over his white turtleneck, and a French sailor’s hat with a red pompom on his white hair. He was holding a soccer ball and he clearly did not want to be there. The children shrieked with laughter. Most of the teachers recognized him, but didn’t let on and spoil the fun.

“Sit down at the piano young man.”

With an unhappy grimace, Marsh plopped himself down, put his soccer ball beside him, and tucked his legs under the bench.

Clarissa corrected his posture and went on to explain what a music student had to learn. Finally Clarissa sat down beside him with great dignity and they played chopsticks.

While the children laughed and applauded the first part of the skit, Marsh took off his sailor jumper and rolled down his trousers. He set the soccer ball on the piano, put the sailor hat on it, and gave the pompom a pat to the delight of the children.

“Now my student is eighteen,” Clarissa said.

Clarissa explained the repertoire of pieces he could now play, as Marsh provided excerpts, all the while flirting behind his teacher’s back with each of the women music teachers in the audience. The young teachers blushed and the older ones laughed in delight, while the children giggled and pointed when a teacher they knew was the subject of his flirtation.

“And now lets see what a hardworking music student can become.”

The lights all went out and then a spotlight came on and there was Marsh wearing his Armani evening jacket with his medal miniatures. He held an Oscar in one hand and a Grammy in the other. Clarissa, still in the darkness, played his ‘High Flight Theme’ so beloved by children. The children jumped up cheering.

The spotlight widened to include the piano. Marsh put his Oscar and Grammy on either side of the soccer ball, then offered his hand to Clarissa to stand her up beside him.

“My name is Marshall Chalfont, and Clarissa is my real life teacher. This Oscar for FantasyLand is dedicated to her.”

Marsh then took off his jacket and sat down at the piano.

Clarissa stood behind him with her hands on his shoulders as he played a medley of his music.

The music teachers had tears running down their faces.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

NEW SUITE FOR A VETERANS DAY CONCERT

from the Ariane Trilogy, Book I, by D'Lynn Waldron ©2002

“I've got a surprise for you,” Marsh said as they got on the bed to watch the TV.

It was the live broadcast of the Veterans Day concert in the Mall in Washington, DC.

Ariane immediately knew they would be playing a piece of Marsh's music, and she settled back in his arms to enjoy it.

When only twenty minutes was left of the concert, which she knew would end with 'The Stars and Stripes Forever' and fireworks, she wondered why Marsh's piece hadn't been played yet.

The Vice-President, who was the official host, came on camera.

“Tonight we are introducing a new work by Sir Marshall Chalfont, 'Memorial to the Allies', which was written at the special request of the President.”

“Oh, Marsh, what a wonderful surprise!”

The stage behind the Vice-President filled with old men who had served with the allied nations in World War II.

The orchestra then began Marsh's suite. It was a beautiful new memorial hymn combined with traditional songs associated with each of the countries that were united in that war.

As soon as the huge audience in the Mall realized what the composition was, they applauded for each country as they recognized its tune, and the old men from those countries waved back.

Marsh had not expected this, and tears streamed down his face.

At the end of the suite, the Vice President came on camera again.

“I know we all want to wish Sir Marshall a happy sixtieth birthday.”

There was an enthusiastic round of applause from the huge crowd in the Mall, and then the band launched into 'The Stars and Stripes Forever'.

Marsh lost it completely, sobbing against Ariane's chest, and she comfortingly stroked his snow white hair, with tears running down her own cheeks.

When Marsh had collected himself he became quietly philosophical.

“It must be very lonely to outlive the rest of your generation and have no one who shares your memories... to be the last veteran of a war everyone else has forgotten. Those old men on the stage have more in common with the German soldiers they fought against, than they do with this generation in their own country.”

“To expand on Henry James, both the past and the future are foreign lands.”

“I wonder if I could express in music what it feels like to be an exile from your own past?”

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

WHAT A COMPOSER CAN DO THAT FREUD COULDN'T

from the Ariane Trilogy, Book I, by D'Lynn Waldron ©2002

“Don't make me out to be more than I am. All I do is write music to make bad movies seem better.”

“I don’t believe that and neither do you.”

“If I ever get pretentious about my music, I will no longer be doing my job, which is to save movies, not the world.”

“When people listen to your 'High Flight Theme' it takes them to a place where they are no longer angry or afraid. You can accomplish in minutes what Freud couldn't do in a thousand hours of analysis.”

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------